Unpaid Community Labour of Black Women

Katie and the Grabbing Back Team

This article is an explainer of Nina Banks’ article, ‘Black Women in the United States and Unpaid Collective Work: Theorizing Community as a Site of Production.’

Sounds like a mouthful? Don’t worry, that’s what our explainer article is for.

Introduction

For a long time now, feminists have argued that domestic work is real work, and that women have historically, and unfairly, had to perform the lion’s share of it. Think of all the work women do in the household – cooking, cleaning, caring and organising. When this work is performed in a market setting, where goods and services are bought and sold, the people doing it are paid for their labour.

Secondly, they’ve argued that the work women do in the household “produces and reproduces material life”. In less fancy terms, this means that the work involves creating the goods and services that we need to keep going. Because of this, they argue that the household is a site of production (a place where stuff gets produced), even though it’s outside of the state and the market.

Feminist economists have argued that understanding the household as a site of production, and household work as real work, is really important for justice and equality: it makes visible the unpaid labour women perform daily; it makes visible the value of this labour; and it shows how unfair all this is: why should women have to take on such a large portion of domestic work, where this work is real work and really valuable, without being compensated for it?

Nina Banks thinks this is all well and good. However, she thinks that the feminist economic framework, where the household gets to be a site of production too, doesn’t go far enough. In particular, it’s theory built up from the experiences of White women, and it doesn’t do much to capture the relevant life experiences of Black women and women from other racialised groups.

Banks argues these women also bear the burden of carrying out collective community work: work that creates the goods and services needed for their communities to survive, and that the state and the market fail to provide. Because of this, we need to make room for the community as an important site of production, and the work undertaken there as real work – unpaid labour similar to that done in the household – in our economic framework.

We’re going to have a look at all this in more detail. Firstly, I’ll give a quick explanation of some of the current economic frameworks Banks discusses, and which she argues don’t leave room for Black women’s unpaid, collective community work. Next, we’ll look at some examples of this work, and I’ll give you some of Banks’ arguments for considering this work real work, and the community as a site of production. Finally, we’ll look at what Banks thinks expanding our economic framework in this way can do for us.

3 Economic Frameworks

There are three main frameworks for understanding and studying economic activity that Banks considers. Here’s a quick summary of all three.

Neoclassical Economics

Neoclassical economists mainly focus on some combination of the state and the market in their economic analyses. For neoclassical economists, the production and consumption and the buying and selling of goods and services happens within the market economy, and also state provision of different good and services. This is still the dominant approach to economics.

Feminist Economics

Feminist economists take a wider view: their analysis involves the household as well as the state and the market. They argue that the household too is a site of production, but one that importantly involves unpaid labour such as cooking, cleaning, and caring.

Heterodox Economics

Heterodox economists take an even broader view, including the social economy as a key site of production. The social economy consists of work performed for social objectives (rather than for profit), and its activities provide for community needs that aren’t provided for by the state and the market. This can include formal, registered organisation like cooperative and non-profit foundations, as well as nonregistered, self-help groups. However, heterodox economists have mainly focused on the first of these two.

Banks argues that all of these economic frameworks don’t capture or help us to understand the unpaid, collective community work performed by Black women and women from other racialised groups. This is because collective community work has failed to be, for any of them, a central or primary site of production. We’ll see soon why Banks thinks it should be. First, let’s look at some examples of this kind of work.

Black Women’s Community Work

In her article, Banks mainly focuses on community work done by Black women in the United States, so here I’m going to do the same. However, we should remember that she thinks a framework which holds community activist work as a key site of production will also capture the experiences of a range of women in a range of countries.

Banks argues that, historically, Black women have engaged in more community work than Black men. Further, they’ve needed to a lot more than White women, because of the difficulties these communities face due to racism. Think, for example: lack of funding, lack of access to opportunities, poor access to public services, to name a few. However, these women’s contributions often go unnoticed and unheralded. Here are a few of the examples Banks gives:

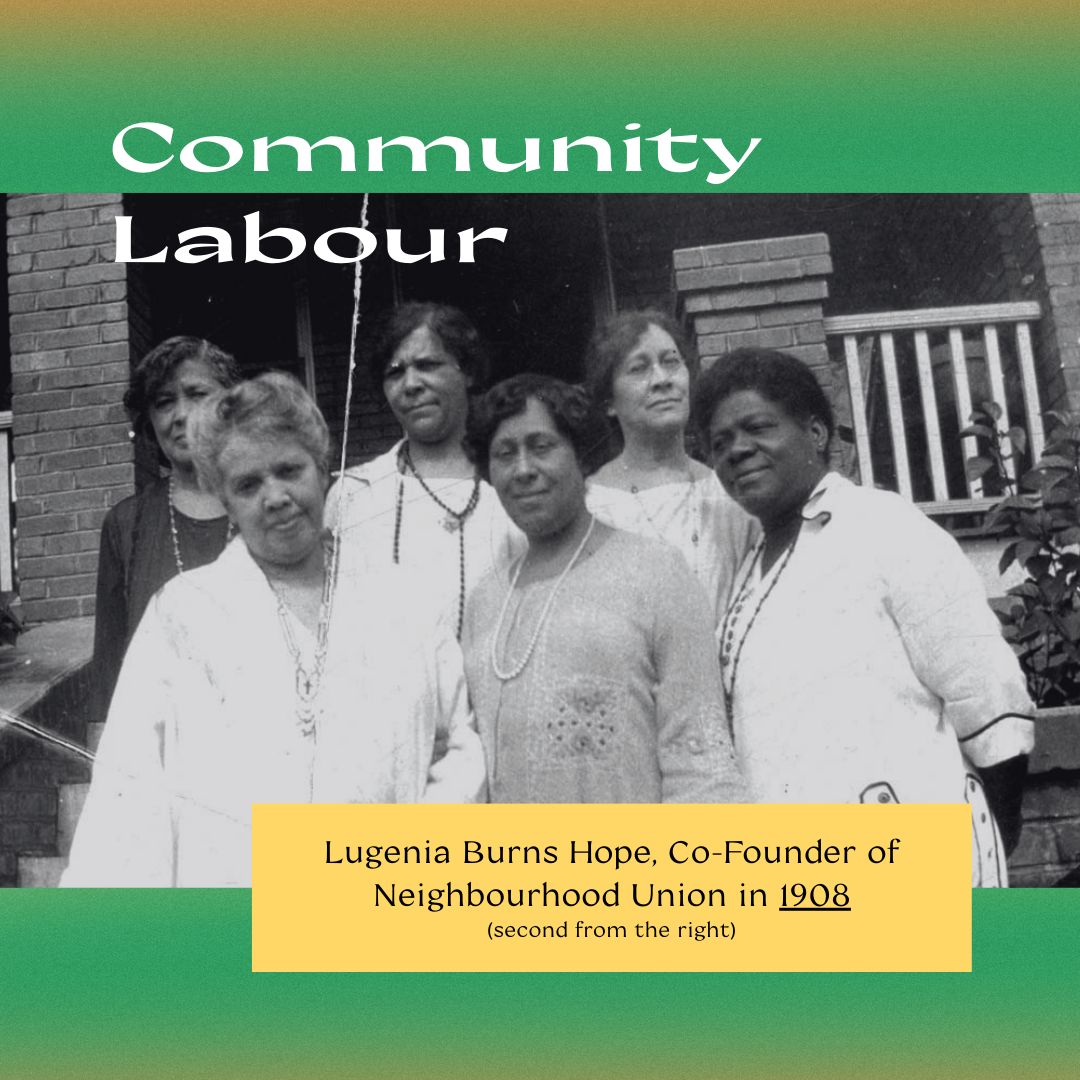

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, Black women created cooperative associations, fraternal orders, and benefit associations that provided services to Black community members. For example, the Atlanta Neighbourhood Union, formed in 1908, collected data on the community needs that had been neglected by White city officials. They used it to lobby for better conditions. Read more

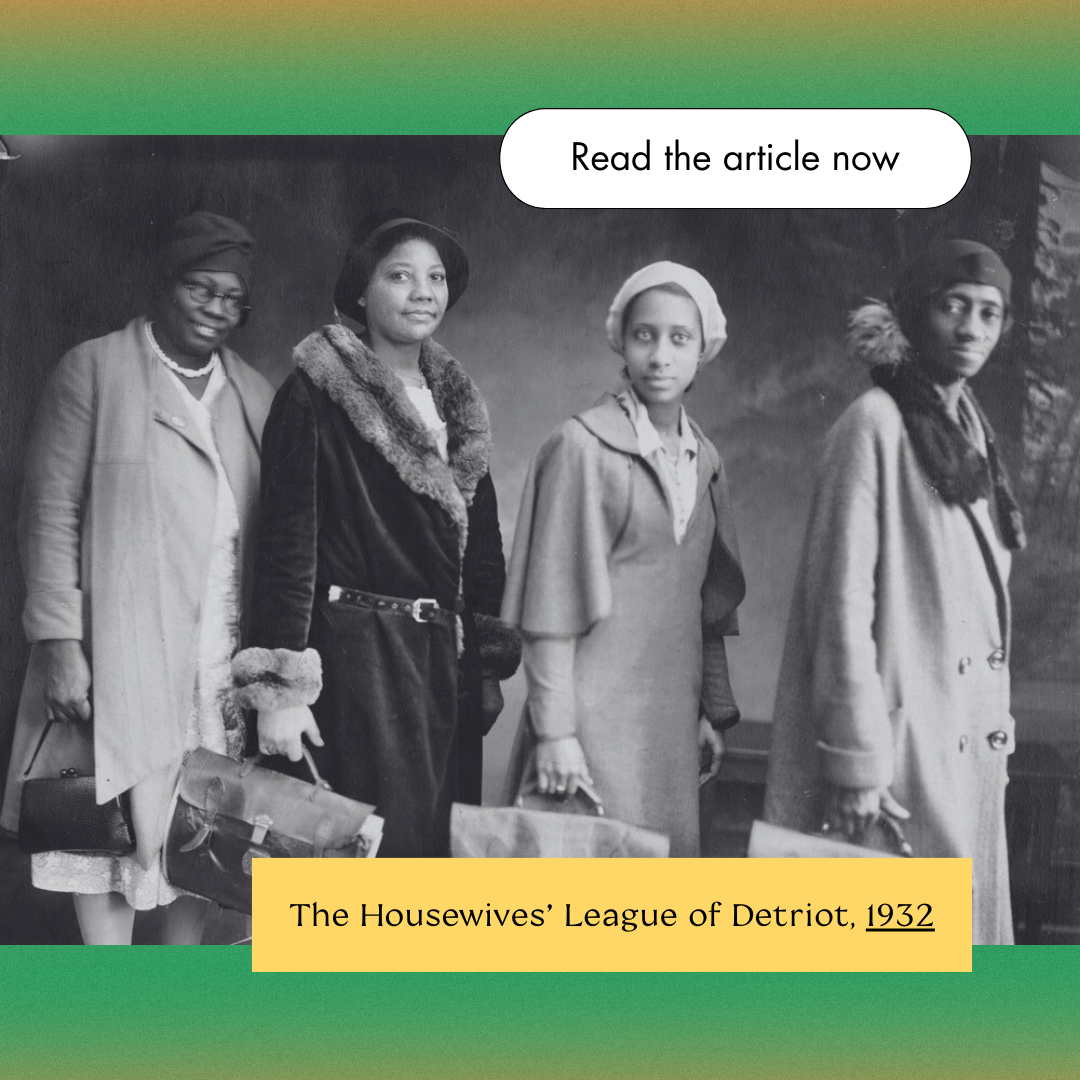

During the Great Depression, a group of African American women formed the Housewives’ League of Detroit, which campaigned to support Black businesses in achieving economic growth and to increase employment. Read more

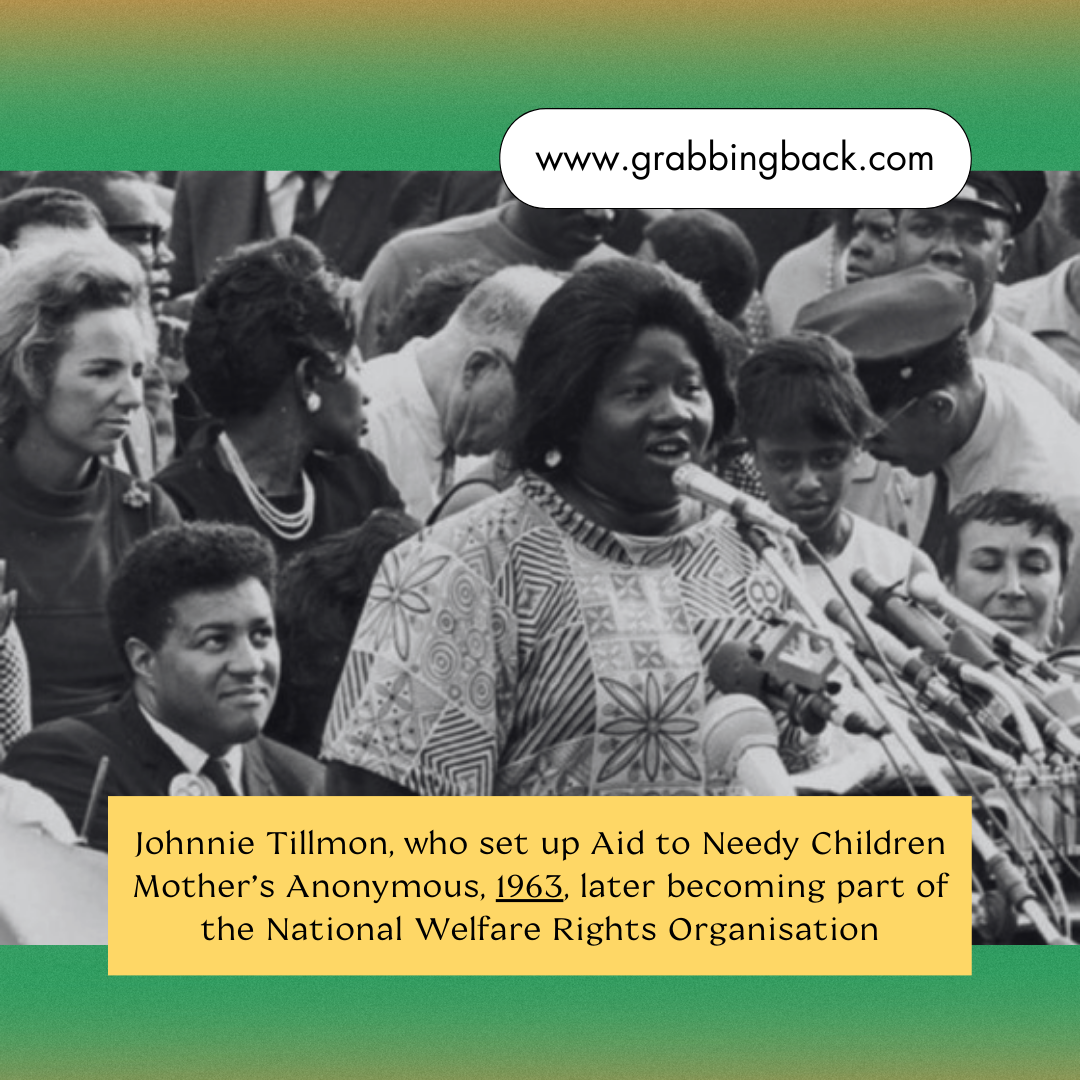

In 1963, a group of Black mothers started Aid to Needy Children – Mothers Anonymous. This group worked to train welfare mothers in how to deal with welfare disputes and difficulties, how to challenge evictions and removals, and in civil rights activism. Read more

Housewives League of Detriot, 1932

These are just a few examples. Banks gives loads of others, as well as examples of work done by women from other racialised groups. If you’re interested, have a look at her article here. For now, this should just give you a flavour of the kind of work we’re talking about.

The Community as a Site of Production

According to Banks, this kind of work has tended to be thought of as political rather than economic. She thinks this is a mistake: the community activism these women are undertaking “produces and reproduces material life”, it creates the goods and services these communities need to survive, and goods and services not provided to them by the state or the market. In this way, it seems pretty similar to the social economy discussed by heterodox economists. Further, since it’s producing all of this stuff, it looks like a site of production.

Secondly, remember the argument that feminists and feminists economists have made about work in the household. One of the reasons they’ve argued we should think of it as real work is that it involves labour that, in a market setting, would be compensated. Cooking, cleaning, and caring are all jobs, after all. Banks thinks we can say something similar here: the work these women are doing involves collecting information, organising meetings, making phone calls to the media and to elected officials, writing letters and op-eds, organising petitions…the list goes on. Again, these are all things that, if channelled through the market, would be counted as real work.

So far then, we’ve got three points:

the community is a site of production,

work carried out to help the community is real work,

Black women and women from other racialised communities bear the burden of carrying out this work.

Expanding the Framework

Banks thinks that this gives us reason to expand our economic framework. Firstly, it would just be more accurate: the work these women are doing involves labour that, in a market setting, would be paid for. It also involves labour that “produces and reproduces material life”. In this way, it seems pretty similar to the state, the market, and the household. Given this, it’s hard to see why it too shouldn’t have a central place in our economic framework: it looks like a framework without it is missing something important.

Secondly, remember that feminists economists have argued that incorporating the household into our economic framework can help us fight injustice and inequality: doing so sheds light on the experiences of women, highlights the value of their labour, and highlights the unjust distribution of labour in the household. However, this framework has done far less for Black women than for White women: Black women haven’t historically been confined to the household in the same way White women have, but rather have often had to go out and work in lower paid jobs, and to perform this kind of community work. However, a framework which includes the community could help us to achieve these things for Black women and women from racialised communities.

For example, doing so could help us understand the interplay between the state, the market, and communities, and to see more clearly how the failings of the state and the market – unjust labour practices and lack of state provision due to racism – as well as gender norms mean that these women must, unfairly, undertake this unpaid labour which is necessary for their communities health and survival. So, you might think something like this: if placing the household at the centre of our economic framework was important and good for White women, then we have all the same reasons to place the community at the centre of our framework for Black women.

Conclusion

This was a super brief intro to some issues in feminist economics. If you would like to learn more about it, take a look at the resources in our reading list for this topic.

The thought here is that, like so much feminist theory, although the work done to fight injustice for women has been good, it just hasn’t done enough to capture the experiences of Black women and women from other racialised groups. Banks thinks her new framework, which gives the community a central place, can help us move on from this.